![]()

The title of this post is rather short and simple but this topic in Safrut is obscure, confusing and very challenging. The scribes usually pay little attention to what ink they use - most will just buy what's offered in the Safrut stores - but there are many opinions and the conclusion is somewhat unclear. There are very few resources on the web in English on this topic and here I hope to organize everything concisely for you.

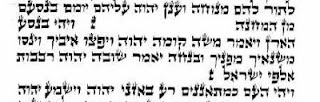

The earliest record we have about the Halachot of ink is brought in the Jerusalem Talmud,

Megilla 12 (פרק א הלכה ט):

הלכה למשה מסיני שיהו כותבין בעורות וכותבין בדיו

One of the Halachot of Moshe taught in Sinai is that you should write (Sta"m) in parchement and write it with ink..

From this we see that a scribe must use ink and not other materials when writing Torahs, Tefillins and Mezuzot. The big question is if this Halacha refers to a specific, "holy" ink or just any black ink.

What's the diference? Well, there are two ways of making ink:

Carbon-based ink is made from soot or charcoal dust...soot was gathered from burning vegetable or animal fats. Charcoal dust was produced by burning vegetable matter such as beech trees or cedars... It is very clear that this was the ink used by Moshe Rabbeinu and onwards until recently. The ink the the Dead Sea scrolls is carbon based.

Iron-based ink is made from oak-nut galls, green vitriol, also called copperas...its chemical formula is FeSO4, 7H2O, that is, iron sulfate crystallized with seven water molecules... This is the ink used by virtually all Jewish scribes in the past few centuries.

If Moshe wrote with a specific ink how can we use something else? The Gemara discusses this topic in,

Eiruvin 13A:תניא רבי יהודה אומר ר״מ היה אומר לכל מטילין קנקנתום

לתוך הדיו חוץ מפרשת סוטה

R. Judah stated: R. Meir laid down that vitriol may be put into ink intended for any purpose except [that of writing]

the Pentateuchal section dealing with a suspected wife.

דתניא אמר ר״מ כשהייתי אצל

ר׳ ישמעאל הייתי מטיל קנקנתום לתוך הדיו

ולא אמר לי דבר כשבאתי אצל רבי עקיבא

אסרה עלי

for it was taught: R. Meir related, ‘When I was with R. Ishmael I used to put vitriol into my ink and he told me nothing [against it], but

when I subsequently came to R. Akiba, the latter forbade it to me.’So here you have a classic Talmudic discussion - Rabbi Akiva against Rabbi Ishmael - about the permissibility of using Kankatum in the ink used for scribal work. So we have two types of ink; with and without this ingredient.

First, we need to understand what is Kankatum. Rashi there identifies it to be "adriment" in French, also known as Atramentum. However most commentators identify Kankatum as Vitriol, which in Latin refers to any metal sulfate but in this case, is identified to be specifically

iron sulfate (also known as Copperas). Ink written with Kankatum is iron-based ink.

So the big question is what is the Maskana (conclusion) of the Gemara and who's opinion we follow in practice in regards to adding Kankatum.

Another way to understand this discussion is if there is a specific "holy" ink that must be used for writing Stam. Those who think that you can add Kankatum believe that any black ink is permissible even tough Moshe used a different ink but those who forbid it do believe that there's a specific "holy" ink and that Moshe in Sinai instructed us to write only with this specific ink.

Since almost every Rishon speaks about this topic, I will limit this discussion to the Halacha Lemaase, that is, practical Halacha. There are three main codifiers - Rosh, Rif and Rambam - and if two of the three follow one opinion, Halacha will follow it as well. So what do they say?

Rosh (Gitin 2:10): (Mei Tarya and) Afatzim can be used, unless the parchment was treated with Afatzim, for then the ink will not be visible.

R. Tam (cited in Rosh Hilchos Sefer Torah Siman 6): Ink made with Afatzim is not called ink. A Mishnah (Gitin 19a) discusses ink and dyes Kosher for a Get. R. Chiya's (our text - R. Chanina's) Beraisa permits Mei Tarya and Afatzim. It adds to the Mishnah. This shows that Afatzim are not called ink!

Rebuttal (Rosh): Afatzim themselves are not called ink, until they are mixed with sap. Then, it can be used to write even on a parchment treated with Afatzim.

We see from the Rosh that even an unusual ingredient like Afatzim (galls) can be used in the ink, as long as is mixed with other ingredient (and that it is black)

Rambam (Hilchos Tefilin 1:4): To make the ink, we gather the smoke of oils, tar, wax or similar things, and knead it with tree sap and a little honey. We soak it very much and pound it until it is like wafers. We dry it and store it. When it is time to write, we soak it in Mei Afatzim or similar things, so if it is erased, it will be erased. This (carbon based ink) is the best ink for Seforim, Tefilin and Mezuzos. If any of the three were written with Mei Afatzim and vitriol, which cannot be erased, it is Kosher.

The Rambam prefers to use the original carbon-based ink but clearly states that iron-based is also good. He, like the Rosh, doesn't think that there's a holy ink that must be used for Stam. For the Rambam, any black durable ink is acceptable.

The Rif is silent in this topic but we already have two views from the three permitting any ingredient to be added to the ink. So the Halacha in Shulchan Aruch is indeed like the Rambam and Rosh:

Shulchan Aruch (YD 271:6): A Sefer Torah must be written with ink made from smoke of oils soaked in Mei Afatzim.

If it was written with Mei Afatzim and vitriol, it is Kosher.

This is the practical Halacha - you can use any ink, although the best one is the original, carbon-based ink. This was the simple part. Now you can fully appreciate the complications if you want:

1. When the Rambam says "If any of the three were written with Mei Afatzim and vitriol, which cannot be erased, it is Kosher." it sounds like it is Kosher Bedieved, that is, impromptu. If so, why do we write today with vitriol (iron-based) if it is only Bedieved? Answer: If a sofer has both inks to choose from, indeed the carbon-based is prefered. But for a few centuries already, we don't know how to make a good carbon-based ink and therefore we are only left with the iron-based ink(Birkei Yosef), which is also good and in such situation it's used even Lekatchila (

Keset Hasofer).

It's interesting to note that even the Teimanim, who always follow the rulings of the Rambam, use the iron-based ink for many centuries already, certainly for the same reason.

Here and there, some innovative scribes tried to come up with reliable carbon-based inks and some had success. It is said that

R' Reuven, a very esteemed Chasidic scribe whol lived some 200 years ago, only used carbon ink and the same is said about

R' Netanel Tfilinsky, who lived in the early 1900's and developed a secret carbon ink that still looks good in his works (people collect them). But the fact is that there hasn't been a reliable carbon-ink for Safrut in the market for many centuries now.

Zvi Shkedi, a Chabad scientist from Scranton (see his knol

here and his

video about this topic), recently started to produce a carbon-based ink that is available for purchase - I purchased a bottle for a try. While I dislike his vitriolic (pun intended) attacks on our esteemed iron-based ink, his work is interesting and perhaps a game changer. I will leave my complaints and my compliments about his Dio Lanetzach for another post.

2. Rabbeinu Tam understands that the conclusion of the Talmud Eiruvin, brought above, is like the opinion that forbids Virtriol (iron-based) ink and therefore he unequivocally states that a Sefer Torah written with iron-based ink is Pasul! Why we don't consider his opinion?This is actually the third instance in Safrut of a discussion between Rabbeinu Tam and his uncle Rashi, who holds that iron-based ink is 100% Kosher. How fascinating is to think that the grandson disqualified the Torah of the grandfather! Remember that their discussions are based in earlier discussions as explained in my earlier posts. Be it as it may, we have demonstrated above that Halacha Lemaase

does not render iron ink Pasul and that's all that matters.

A very liberal blogger asked a seemingly powerful question. Why do some people put on a second pair of Tefillin that is made according to Rabbeinu Tam if the scribes today write the Tefillin parchements with iron-based ink which is Pasul according to Rabbeinu Tam himself. If you are trying to follow Rabbeinu Tam you should write his Tefillins only with carbon-based inks!

The question is better than the answer. The answer is that the opinions of Rabbeinu Tam throughout the Talmud are not necessarily interdependent. For instance, the first discussion between Rashi and Rabbeinu Tam is about the shape of the letter Chet (see

here) and the Ashkenazim follow Rabbeinu Tam. In the other hand, there's another discussion about how we should manufacture our Tefillins - once again between Rashi and Rabbeinu Tam - and the Ashkenazim follow Rashi's opnion. So they put Rashi's Tefillin but write the letters Chet in it according to Rabbeinu Tam. You see clearly that Halacha will not always follow Rashi nor Rabbeinu Tam; Halacha is dealt in a case by case fashion.

I only wonder if the Belz dynasty, who have a history of adering to Rabbeinu Tam's opinions (as mentioned

here), are Machmir to write Stam with carbon based inks. Anyone knows?

.jpg)